He defined the “critical museum” as a forum engaged in public debate, an institution forging democracy, one in a state of constant antagonism, and, perhaps most importantly, one capable of asking questions of itself. A few years ago, the art historian Piotr Piotrowski called for a “critical museum,” as opposed to the museum-as-shrine or museum-as-entertainment. It is symptomatic of this crucial moment in Poland that three art institutions in Warsaw became interested in the same period of history and in its contemporary resonances, in the context of memory, trauma, and social justice.

2015.įrom the exhibition "Reconstruction Disputes," Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw. The dramatic, romantic history of Królikarnia, Dylewo and Polesie may have seduced viewers at first, but the photos and the sculptures, the ruins and the dust, only uncovered their roots in private privilege - something we cannot learn watching Downton Abbey.… Tymek Borowski. But any nostalgia for the estate’s past eventually gave way to the acrid present. At the “Estate,” the curators used one room to compare Chomętowska’s photos of Warsaw’s ruins with documents about the history of the Królikarnia palace itself: its destruction, nationalization, reconstruction and conversion into a museum. The ruins here thus became the context for two nostalgias - German nostalgia for East Prussia (now within the borders of Poland) and Polish nostalgia for Polesie (now within the borders of Ukraine). She even happened to be a guest at the Królikarnia palace before the war, filming the lavish lives of its inhabitants, though by 1944 Chomętowska had to rescue her negatives from the burning city. Born to a wealthy family in east Poland, she photographed both peasants in the Polesie region (now within the borders of Ukraine), and the local aristocracy. These German ruins on (now) Polish territory were juxtaposed with photographs by the Polish artist Zofia Chomętowska. A bust of one von Rose fell prey to Russian soldiers, its nose and ears shot off. A bronze bust of Dante was consumed by a disconcerting melanoma. The marble heads seemed to have been burned alive. Królikarnia’s exhibition was comprised of these disinterred artworks, organized into a huge installation.

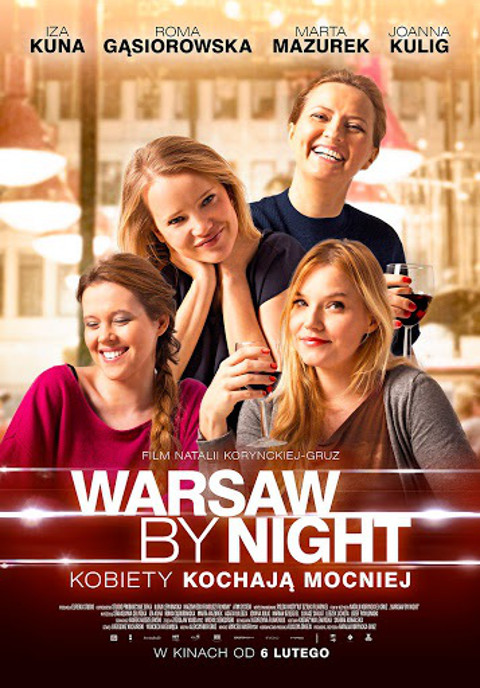

Dylewo is now in ruins, and the remains of the sculptures had to be unearthed the same way ancient treasures are excavated. The estate was owned by the van Rose family, and their vast collection of sculptures, mostly by Italian artist Adolf Wildt, was left behind when the family fled to the West, the Red Army at their heels. Królikarnia’s director, Agnieszka Tarasiuk, in collaboration with a team of researchers, artists and curators, put together the exhibition “Estate,” which looked at the history of Dylewo (or Döhlau), a country manor in what was then East Prussia. Ruins lay at the heart of three exhibitions in Warsaw last year, one in a decidedly bucolic setting: the 18th-century palace of Królikarnia, which displays sculpture from the National Museum in Warsaw. From the exhibition "Estate." Królikarnia, Warsaw, 2015. Warsaw by Karol Sienkiewiczīust from the collection of the von Rose family, recovered from the ruins of the palace at Dylewo.

Shop Menu Even Magazine Global perspective on contemporary art and culture III.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)